Percentage rent using different partial year methodologies

May 28, 2017

Percentage rent is where a tenant pays a percentage of its sales once it has exceeded a certain base level of sales. The better a tenant does, the better the landlord does. If the tenant does not exceed the base level of sales, or the breakpoint, the landlord does not receive percentage rent.

In most cases, the tenant reports sales and pays percentage rent based upon its Lease Year. Lease Year is defined within the lease, most often defined one of three periods: 1. A Calendar Year (1/1-12/31), 2. A period running 2/1-1/31, and 3. A period ruining 12 full months from the commencement date (if it is the first of the month) or from the first day of the month following the commencement date (if the commencement date does not fall on the first of the month).

Calculation of percentage rent for full lease years is simple and straightforward. Take sales for the full lease year less the breakpoint for the full lease year, and multiply that excess times the percentage rent rate to determine percentage rent. However, when a partial lease year (a period less than 12 full months) is involved, a lease must specifically address how percentage rent is calculated because the methodology applied could provide wildly different amounts due.

Consider why partial years would be an issue. With exceptions for certain categories of retail and certain types of properties, most retailers will do a disproportionate amount of sales in November and December. Typically, we set an expectation of about 12% of sales in November (weighted toward the latter part of the month) and 19% in December. Think about that. If a tenant opens on 12/1, they are going to do about 19% of their annual sales in just over 8% of the year. Depending upon how the lease addresses percentage rent for that period (if the lease year end were 12/31), the tenant could pay wildly different amount of percentage rent.

While there is no limit to the number of ways that percentage rent for a partial period can be calculated, there are three 「typical」 methods applied in the industry – 1. True partial lease year, 2. Extended lease year, and 3. Extended partial lease year.

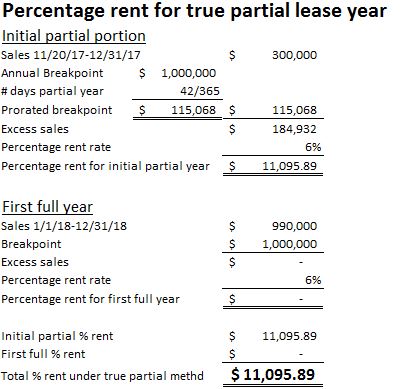

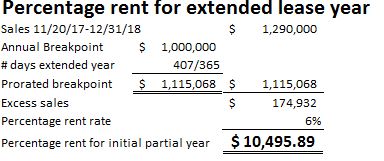

A true partial lease year requires that sales for the partial lease year be compared against a breakpoint calculated using the annual breakpoint prorated for the number of days in the partial period. Opponents of this method argue that the tenant is unfairly penalized higher amounts of percentage rent because the tenant opened during the busiest time of year. Proponents of this method argue that the tenant did not pay rent during the slowest times during the year and got the benefit of opening during the busiest time of year. An extended lease year combines the initial partial lease year with the first full lease year. To a certain extent, this method allows for the fact that there is often an artificial bump in sales when a tenant first opens. The final method, the extended partial, still bills for the partial period, but uses sales for the first 12 months against a breakpoint for the first 12 months, and then prorates the percentage rent that would be due for this so-called reference year by the number of days in the partial lease year. This method began surfacing around 20 years ago and is slowly becoming the standard in regional mall leases. It can be found in strip centers, but the first two methods are still much more common in open air centers.

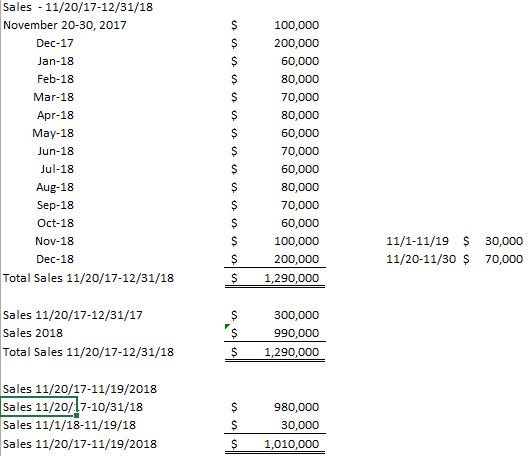

Reflected in the following slides, I have calculated percentage rent for an initial partial lease year and a first full lease year using the same exact sales figures and a requirement that the tenant pays 6% of sales aver a $1,000,000 annual breakpoint.

Sales

True partial lease year

Extended lease year

Extended partial lease year

As you can see, percentage rent for the periods using the exact same set of numbers can range from a low of $69 to a high of $11,096. Therefore, whether you are a landlord or a tenant, it is imperative that you understand how percentage rent is required to be calculated for partial lease years.