Taxes and insurance addressed in CAM – and then again, separately

May 5, 2019

It’s not unusual to see terms referenced several times throughout a lease. Often, it will be a definition of a concept in one clause and the use of that defined term in another. But, sometimes, it can be confusing as to why a term is mentioned multiple times.

Case in point is when insurance or real estate taxes are included in the definition of common area maintenance (CAM). The lease may require the tenant to pay a prorata share of CAM – so the tenant is paying a prorata share of insurance and real estate taxes through CAM. But the lease may actually continue with a separate real estate tax and a separate insurance section, each requiring the tenant to pay a prorata share. We addressed this issue a couple of years ago in a blog (Common area taxes and liability insurance). But, this week, we were working on an acquisition that put a slightly different twist on this.

A brief recap – When you see taxes and insurance addressed as part of CAM and then separately, a light should go off. The common area portion of real estate taxes and the common area portion of insurance are included in CAM, whereas the taxes and insurance on the leasable portions of the center are billed as separate charges. Insurance and taxes on the parking fields, on the mall areas, on the sidewalks, on all of the common area are billed in CAM. But, the insurance and taxes on the actual leasable spaces are billed separately. The earlier blog addresses methods of calculating the common area portions of those charges.

So what’s the twist that warrants a new blog. (I apologize in advance, it gets a little convoluted here!)

For this particular tenant (a junior anchor, so sizable), the tenant’s CAM was capped while the separate insurance and real estate tax sections were not. And, unlike the majority of cap clauses negotiated into leases, this clause did not have the most common exceptions from the cap for insurance, utilities, taxes and snow removal. (It would read something to the effect of “Tenant’s share of Controlled CAM shall be capped at 5% over the Tenant’s share of Controlled CAM for the prior year. Tenant shall pay its full prorata share of Uncontrollable CAM. Uncontrolled CAM shall include insurance, utilities, taxes and snow removal.” There are quite a few other blogs that address cumulative vs. non-cumulative caps as well that must be considered.) The reason that those exceptions typically exist is that, as the language implies, the landlord has no control over certain expenses (or limited control – there is always some control) and the landlord should not be penalized for exceptional increases to those expenses.

What does that mean then? That means that the common area portion of taxes and insurance is capped, while the premises portion of those charges is not capped. When you consider the requirements of the lease item by item, the calculation is fairly clear. But, in this case, the requirements were not consistently applied.

When billing the tenant, the landlord included ALL real estate taxes and ALL insurance in CAM, and applied the cap to the ENTIRE CAM charge – no exclusion of and portion of taxes or insurance from the cap.

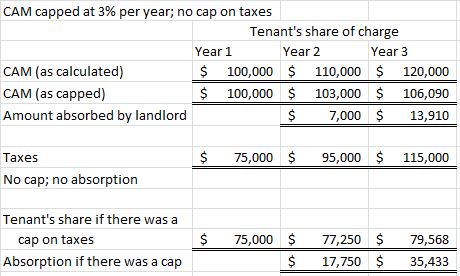

Most typically, you would expect that, if the landlord capped a charge that was not supposed to be subject to a cap, the landlord had potentially underbilled a tenant. Let’s take the following example of CAM subject to a cap and taxes not subject to a cap.

In the example above, with no cap on taxes, the landlord would absorb about $21,000 in years two and three for CAM, but nothing for taxes. However, if taxes were also capped, the landlord would absorb another $52,000. That is a fairly good example of why taxes might be excepted from a cap – taxes increasing materially but the landlord having no control.

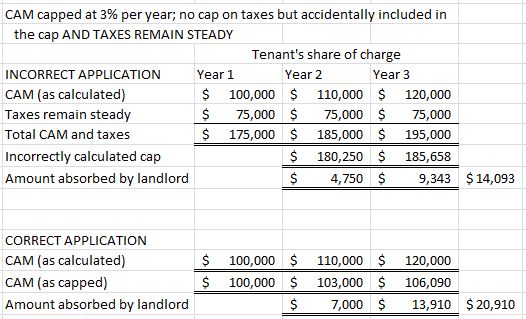

However, consider an example where taxes are remaining steady. Like the selling landlord, if the landlord incorrectly included taxes in the calculation of the cap, the landlord would have absorbed only $14k because of the cap rather than the $21k it should have absorbed.

So in this latter example, the landlord would have overstated the property’s NOI by about $4,600 in year 3 (the difference between absorbing $13,910 if billed correctly and $9,343 as billed).

Further complicating the issues this week was the fact that for purposes of billing the tenant, the landlord had included all taxes in the cap. However, when presenting the cash flow to prospective buyers, the landlord excepted ALL taxes from the cap, not just the premises portion.

The end result in our particular instance is that the seller did, in fact, overstate cash flow (when we might have expected the opposite to have been true) by including taxes in CAM, subject to a cap.

Unfortunately, sometimes the application of lease language can result in a cash flow that varies from what was intended.