Premises trash and utilities vs. common area trash and utilities

June 9, 2019

It is not uncommon for a landlord to provide or arrange services for the actual tenant premises within a shopping center. Perhaps the tenants are provided water services to their spaces through one water main/meter, or the landlord arranges for trash removal from the premises rather than having each individual tenant arrange the service themselves. Or in some cases, there may even be electricity or HVAC provided by the landlord to the individual premises.

In the majority of leases, these services for the tenant’s own premises are addressed in a utilities section of the lease (with language that may read something to the effect of: “Tenant is responsible for all utilities consumed at the premises. If the landlord provides any of these services to the tenant, the tenant will purchase the same from the landlord at rates not greater than the tenant would be billed if the tenant were billed directly.”) Trash removal can sometimes be found in the utility section, the tenant maintenance, or even in the rules and regulations section/exhibit of the lease, containing similar responsibility language.

But this provision of services by the landlord can sometimes cause confusion, as it did three separate times this week. These services provided to the premises are NOT common area expenses. In most shopping centers, the landlord does provide water to the common areas of the center, and the cost of that water is absolutely CAM. However, water provided to the tenants for use within their premises is not CAM. It is a premises utility. The landlord’s removal of trash/emptying of common area trash receptacles is CAM, but the cost of removal of the trash from the individual tenant premises is a tenant expense. If the landlord happens to provide for or arrange the trash removal service, it is still a tenant expense, not CAM.

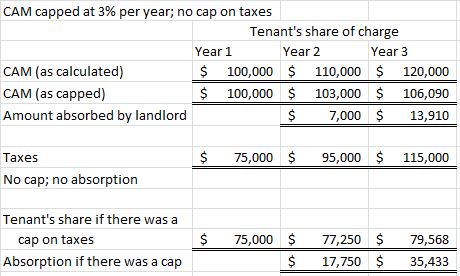

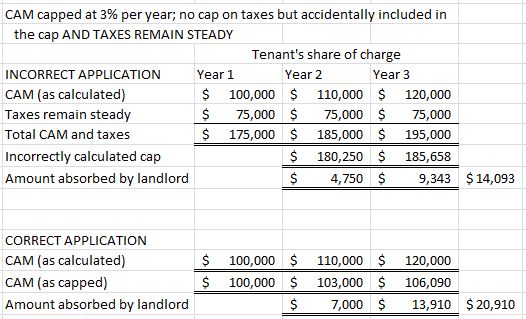

Often in attempt to simplify billings to the tenants, it is not uncommon for landlords to include these expenses in CAM and bill the same prorata shares used for CAM for these additional expenses. However, this attempt at simplification can cause some major errors.

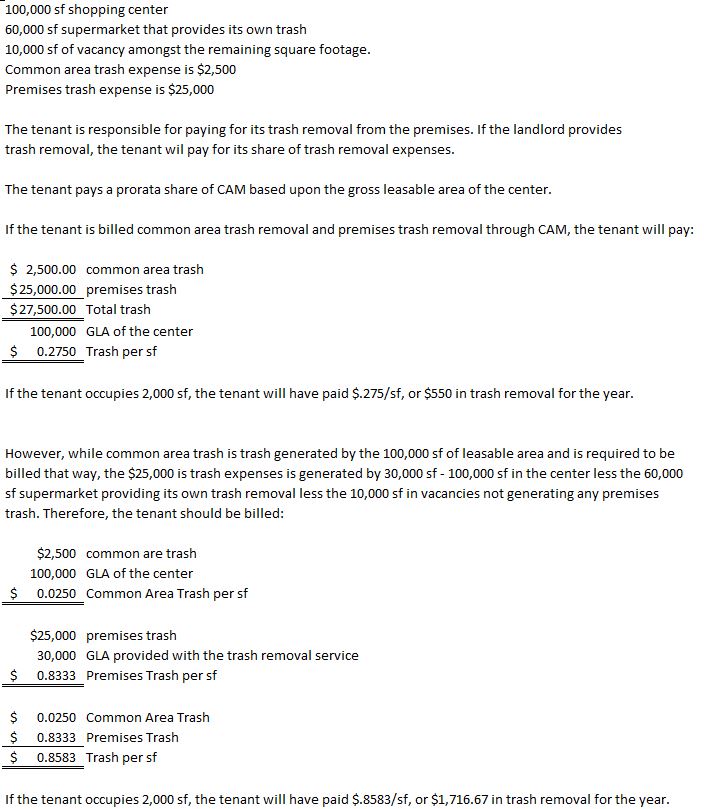

One group of tenants to jump on this error in methodology is big boxes and supermarkets. So often, despite what is happening at the rest of the center, the big boxes do not participate in the landlord’s trash program and have also made the installation of separate meters for water or electricity a key component of their leases. Therefore, if the landlord were to bill trash or premises water through CAM, and those big boxes arrange and pay for their own trash removal and water directly, the landlord would be double dipping. Not that it doesn’t happen, but big boxes challenge this method regularly. (I don’t want to get off topic, but if the landlord gets one invoice for trash or water that covers premises trash removal and common area trash removal (or water), often the landlord and bid boxes will come to an agreement on an allocation of these invoices among premises and common areas (often 90/10 or 95/5 – so a $50,000 trash invoice might get allocated $5,000 as common area trash permitted to be included in CAM, and $45,000 as premises trash not permitted to be included in CAM).

This CAM inclusion method often causes tremendous amount of absorption by the landlord. If a tenant’s CAM method is leasable with no exclusions, a landlord might bill trash that way (by including it in CAM). However, in that center, if there was a major that provided its own trash removal and did not participate in the expense, and there was some vacancy, the landlord would be absorbing a significant portion of the expense. Take the following example:

In our example, if the landlord bills the tenants premises trash using the CAM reimbursement method (GLA with no exclusions), the 30,000 sf of tenants that are provided with the trash removal service will have paid $7,500 (30,000 sf x the $.25/sf portion of the charge attributable to premises trash). The landlord will have absorbed $17,500 (major (60,000 sf) plus vacancy (10,000 sf) = 70,000 sf x $.25/sf. What does that mean? We as the landlord lose $17,500 per year, or, at an 8% cap rate $218,750 in value ($17,500/8%).

All because we tried to simplify the billing method.

In a specific example from this week, the tenant’s actual CAM charges were $3.70/sf, but CAM was capped at $3.47/sf. But over and above the $3.70/sf, the landlord was billing premises trash through CAM – another $.25/sf (reflected as $3.95/sf – $3.70 + $.25). The tenant expected all charges to be capped at $3.47/sf. But that $.25/sf was not CAM! So, ultimately, the tenant was responsible for $3.47 + $.25 = $3.72/sf. This was a 16,000 sf tenant. That difference was $4,000 per year. One lease, $4,000 per year.

It really does pay for you to know the difference between common area services and premises services!